How to Make a Random Square

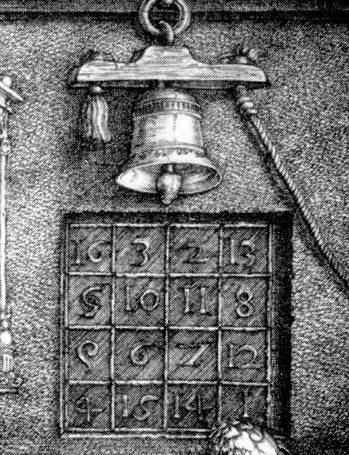

I have noticed that it has been difficult to elucidate a method for systematically creating even-ordered magic squares of any but the most basic kind. I don’t know why this is, since the art has been alive in Europe for at least 600 years, and probably longer in other cultures. There are a few methodologies out there, but they are perfunctory. Such as, this method offered by Reichmann (1957), which tells us little more than to write the numbers down from 1 to 16 and reverse the order of the diagonals:

1 2 3 4 16 2 3 13

5 6 7 8 ====> 5 11 10 8

9 10 11 12 9 6 7 12

13 14 15 16 4 14 15 1

Well, only a limited number of magic squares are possible that way. You can reverse the order of the numbers, or write the numbers in order down the columns instead of the rows, followed by a similar reversal of the diagonals (these would not be considered to be unique solutions, since these methods amount to mirroring or rotating the square).

After some playing around with known 4×4 magic squares (thanks to the thorough resource offered here), and using some simple rules, I think I may have come upon a method on my own. I would suppose that it could not generate all magic squares possible, but I don’t intend to offer a complete solution. I estimate that I would be able to generate maybe another 10 or so magic squares with this method. The intent here is to allow the reader to create a 4×4 magic square sitting down at a table with little more than pencil and paper. I am sure this methodology is published elsewhere, but I wasn’t able to come up with anything.

I just have a few simple rules in coming up with the method. First of all, all of the 16 numbers are the result of a sum of two smaller numbers a and b, where a is a number from 1 to 4 such that a = {1, 2, 3, 4}, and b is a multiple of 4: b = {0, 4, 8, 12}. All 16 unique numbers generated will be the result of adding a number from set a to a number in set b.

The numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4 are the result of adding set a to 0 in set b.

The numbers 5, 6, 7, 8 come from adding set a to 4 in set b.

The numbers 9, 10, 11, 12 come from adding set a to 8 in set b.

And the numbers 13, 14, 15, 16 come from adding set a to 12 in set b.

My solution is inspired by Reichmann’s (1957) work on odd-ordered matrices. This solution on even-ordered matrices is quite different than for odd-ordered matrices, but the idea of adding two matrices and getting a magic square appealed to me, so I went with that basic idea.

The first matrix uses numbers from set a, in the following pattern:

4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4

1 2 3 4

4 3 2 1

These numbers may be randomized, but I’ll just stick to numeric order for now. The second matrix is composed of the numbers of set b arranged in a pattern reminiscent of the Durer square:

12 0 0 12

4 8 8 4

8 4 4 8

0 12 12 0

The sum of the two matrices has all the magic of the Durer square, and consist of the unique numbers 1 to 16:

16 3 2 13

5 10 11 8

9 6 7 12

4 15 14 1

In fact, it is the Durer square itself. Now that we know it works, what about mixing things up? Take note of the patterns. Let the first matrix represent numbers {a, b, c, and d} belonging to set a; and {e, f, g, and h} belonging to set b. whatever randomization is chosen, the numbers must fit the following scheme:

a b c d e h h e

d c b a f g g f

d c b a + g f f g

a b c d h e e h

a, b, c, and d may be any permutation of the numbers 1 to 4, without apparent limitation. The second and third rows on teh first matrix are the reversals of the first and fourth. The second matrix, however is much more restricted. Considering e and f to be one pair; g and h to be another pair: 12 can only be paired on the same row with 0; and 4 only be paired with 8. Otherwise, no joy.

So, on with a randomized square: let a = {3, 1, 4, 2} and b = {8, 0, 12, 4}

3 1 4 2 8 4 4 8 11 5 8 10

2 4 1 3 0 12 12 0 2 16 13 3

2 4 1 3 + 12 0 0 12 = 14 4 1 15

3 1 4 2 4 8 8 4 7 9 12 6

What about a = {2, 4, 1, 3}, and b = {4, 12, 0, 8}

2 4 1 3 8 4 4 8 10 8 5 11

3 1 4 2 12 0 0 12 15 1 4 14

3 1 4 2 + 0 12 12 0 = 3 13 16 2

2 4 1 3 4 8 8 4 6 12 9 7

You may also treat sets a and b oppositely, while randomizing. This time the restriction is on matrix a — 4 pairs with 1, and 2 pairs with 3:

3 2 2 3 8 12 0 4 11 14 2 7

4 1 1 4 4 0 12 8 8 1 13 12

1 4 4 1 + 4 0 12 8 = 5 4 16 9

2 3 3 2 8 12 0 4 10 15 3 6

The reason I say these squares are limited to about 10 or so, is because as you can see, the individual rows or columns end up being about the same — at best, a shuffling or reversal the same rows found in the Durer square. There are at best 24 such squares, not subtracting tilted (squares the same when laid on its side) or reflected squares (where the squares are mirror images of each other). All that might be said, is that we may have discovered all the ways a magic square may be constructed with the same “hyper-magic” as the Durer square, which may be a pretty cool thing to say actually. It’s just that my goal was more ambitious at the start. I will refer to the set of 4×4 hypermagic squares built on the same rules as “the Durer series.”

Any known magic square, however, is the result of a unique combination of the basic squares built on sets a and b. Respectively, I will call the matrices A and B. This allows us to work backwards from a 4×4 square we know is magic, and discern any patterns. The above squares were done that way. What patterns can be observed for the following square, which this website offers as #379 out of 900 or so others?

Matrix "A" Matrix "B"

13 12 6 3 1 4 2 3 12 8 4 0

10 5 11 8 2 1 3 4 8 4 8 4

7 16 2 9 = 3 4 2 1 + 4 12 0 8

4 1 15 14 4 1 3 2 0 0 12 12

One may discern a pattern here, but it is not all that obvious, especially for the square built on set b. It doesn’t seem to resolve itself into simple rules and patterns the way the Durer series of squares did. Also, you might have noticed that this square is not quite as “magic” as the Durer series, though all rows, columns, and both diagonals give you 34.

But I do notice that in matrix A the last column is a reversal of pairs of the first column. Also, the third column is built on the middle numbers of the first column, and the second column are built on the middle numbers of the last column.

What of Matrix B? The first and last columns are reversals (of all 4 numbers, not of pairs), the second and third both start with the middle two numbers, then first, then last from their adjacent end columns: “e f g h” becomes: “f g e h”.

When I tried to build on these rules, I got duplicate numbers in my squares (and with that, some missing numbers). It would appear that the observable number patterns in such squares are limited to getting you maybe 4 to 8 unique squares, then you have to make a new set of rules each time. With over 900 squares discovered (give or take a duplicate or two), that’s a lot of rules. The total number of 4×4 squares, both magic and not, are equal to 16! = 21 trillion possible squares. Finding all possible magic squares, weeding out any duplicates, reflections, and sideways duplicates would seem a tad non-trivial. Even at the website I referred to for these squares, it has been shown that the number “924” claimed as the number of possible 4×4 magic squares, might be too high, due to some duplicates found. Their scripts took just under 25 seconds to generate and check these squares — but just to check them for magic, less so for duplication, which sounds like it would take more computer time.

Visits: 111

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recently, I’ve been hit (my website that is) by someone possibly checking his plethora of links from his/her website, and when I back-traced it, I find this

Recently, I’ve been hit (my website that is) by someone possibly checking his plethora of links from his/her website, and when I back-traced it, I find this